Child-bearing, always accepted as a natural process, tended to be treated with

dispassion but also brutality. At the height of early civilisations – Egyptian

then the Greek and Roman civilisations - methods of caring for the

child-bearing woman were well developed. However, with the decline of the Greek

and Roman civilisations the care of women deteriorated and the practices

developed by the Greeks were not heeded in Europe. Procedures in childbirth did

not recover until the sixteenth or seventeenth century.

METHODS OF

HASTENING LABOUR

Among the Greeks at the time of Hippocrates the

methods of assisting the woman in labour were often brutal. The woman was

sometimes repeatedly lifted and dropped on a couch.

This method of tying the woman to a couch, which was then

turned on end and pounded against a bundle of faggots on the ground, was

finally abandoned by the Greek physicians amongst other aggressive procedures

Accordingly,

the treatment of child-bearing women was considerably neglectful. During

medieval times the mortality rate for both mother and child rose to a uniquely

high level due to indifference to the suffering of women and to the low regard

for the value of life.

This

period was characterised by the fervour of religion and the squalor of daily

life, consequently nothing was done to overcome the enormous mortality of

mother and child at birth. Typical of this age were the attempts to form

intrauterine baptismal tubes, by which the child, locked by some difficulty in

the womb, could be baptized and its soul saved before mother and child were

left to die.

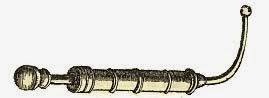

BAPTISMAL SYRINGE

For

applying this rite to infants before birth in cases of difficult labour. This

particular syringe was designed and described by Mauriceau in the seventeenth

century, and Laurence Sterne, in Tristram

Shandy, quotes the original description in full. This syringe was the

'squirt' of his 'Dr. Slop'. In some designs the opening of the nozzle was made

in the form of a cross to add sanctity to its use.

AN

OBSTETRICAL CHAIR

The obstetrical chair upon which women sat during

childbirth is mentioned in the Old Testament. The Greeks occasionally used a

special bed or couch for this purpose, but the chair continued in general use

until the 17th century and was often used as late as the 19th century. This

particular design was recommended by Eucharius Roslin in 1513.

Mauriceau of France in the seventeenth century

started the innovation of using a bed for childbirth.

OBSTETRICAL

CHAIR IN USE

A reproduction of a sixteenth-century woodcut

appearing in The Garden of Roses for

Pregnant Women, by Roslin.

In

Medieval times religion took over the practices of the midwives, thus the

Dominican monk, Albert Magnus (Albert von Bollstadt 1193-1280 ), wrote a book

for the guidance of midwives, and the Church councils passed edicts on their

practices. These instructions and edicts were not, however, for the better care

of the child-bearing woman, for the relief of her suffering or the prevention

of her death. They were designed to save the child's life for a sufficient time

to allow it to be baptized. The Council of Cologne in 1280 decreed that on the

sudden death of a woman in labour her mouth was to be kept open with a gag so

that her child would not suffocate while it was being removed by operation.

By the

beginning of the Renaissance practices improved little. Even in a normal

delivery the woman often died from infection or eclampsia. In difficult labour

she was left to die or butchered to death if her midwife was so inclined, or a

rogue 'surgeon' could be found to assist the slaughter. As a rule the matter

was left entirely in the hands of the midwife, and in 1580 a law was passed in

Germany to prevent shepherds and herdsmen from attending obstetrical cases. An

indication of the advancement in care of the childbearing woman and the

appalling conditions it had advanced from.

FIFTEENTH-CENTURY

NURSE AND CHILD

From 'Versehung

des Liebs'. Accompanying this picture were the following directions for

selecting a nurse ( translation is from Ruhrah, Pediatrics of the Past) .

"At times it happens that from

various causes the Mother cannot suckle the child herself. In such a case one

must choose a nurse for the child. Her qualifications should be as follows.

The

nurse should be of shapely stature, not too young and not too old. She must at

all times be free from illness of eyes or body. Moreover, her nature must be

such that there is no defect in her body. Mark also, that she must be neither too slim,

nor too plump. If there should be any defect in her, the child would incline

towards it.

She must have a good character, modest, chaste and clean.

Her food

should be in conformity with the following directions, so that the milk may

remain fully nourishing. I prescribe her to eat white bread and good meat, also

rice and lettuce every day. Almonds as well as hazel nuts she should not do

without. Her beverage must be pure wine; and in moderation must be used in

bathing. Nor must she do much labour.

In case her milk should give out, she

must not forget to eat peas frequently and in quantity, also beans, and in

addition gruel which should be boiled in milk beforehand. She must also rest

and sleep a good deal so that the child may thrive on the milk. Moreover, she

must carefully avoid onions and garlic; as well as any bitter or sour food and

any dish containing pepper.

She must eat no over-salted food, nor anything

prepared with vinegar.

Love's intercourse she must also avoid or go in for it

very moderately. For in case she should become pregnant, her milk would be

harmful to the child. In order that the child may not be harmed in such a case,

one must wean it from the milk."

This

scenario was for the privileged few because this was a time when public,

domestic and personal hygiene was appalling. The walled cities were for the

most part densely crowded and had no drainage. Filth accumulated in the unpaved

streets. The houses were described by Erasmus as containing open cesspools,

their floors were strewn with refuse, and in them was a pestilence of flies and

vermin. They were indeed sinks of filth and infection.

Ancient

Rome had paved streets, Paris had none until the eleventh century and London

had its first paved streets in the sixteenth century. In that same century

Frankfurt-on- the-Main began requiring each house to have a ‘privy’ and ordered

that the pigpens of the city should be cleaned.

Eucharius

Roslin, of Worms, in response to the wishes of Catherine, the Duchess of

Brunswick, wrote a manual from which the ignorant and careless old women who

made up the midwives might learn to conduct their work in a safer and more

efficient manner. This book was published in Worms in 1513 and contained

nothing that was new, but did bring to light the work of the Greeks; it was,

however, marked with the superstition of medieval medicine, and with the

horrible doctrine of medieval surgical midwifery.

The

prejudices which at that time existed in the minds of people, particularly in

cities, against the slightest participation of males in the practice of

midwifery, were so great that Roslin, who had probably never seen a child born,

may have felt something of the humour of his position, for the title of his

book was The Garden of Roses for Pregnant Women and Midwives. The book,

nevertheless, accomplished much good; it was extensively plagiarised by later

authors and was translated into Latin, French, Dutch, and English - in which

the title became The Byrthe of Mankynde.

EUCHARIUS

ROSLIN PRESENTING HIS BOOK TO THE DUCHESS OF BRUNSWICK

A PAGE FROM 'THE BYRTHE OF MANKYNDE' - WILLIAM

RAYNALDE'S ENGLISH TRANSLATION OF ROSLIN'S BOOK ON MIDWIFERY

The

exclusion of men from the study of child-bearing women tended to reach

fanatical extremes. In 1522, Dr Wertt, of Hamburg wore the dress of a woman to

attend and study a case of labour; he was punished for this lack of reverence

by being burned to death.

Three Kids Gripped By Evil By Polly Mullaney

Amazon Kindle, Amazon paperback |

No comments:

Post a Comment